1 Corinthians 9:16-23 (first published 5 February 2006)

Isaiah 40:21-31 (first published 5 February 2006)

The region of Palestine gets its name from a group of people who migrated to the land from the Greek isles to the West at about the same time as the Israelites came into the land from the East. The Philistines quickly gave up their Indo-European language in favor of the Canaanite language spoken by the earlier inhabitants of the land. Over time, they also adopted Canaanite gods and worship practices. After the Assyrians conquered their cities in the eighth century B.C.E., they eventually ceased to exist as a coherent, self-identified group of people. They merged into the surrounding society, so that today no people anywhere identify themselves as descendants of the Philistines. The name of the territory lingers, but the people no longer exist. The same is true of the Edomites, Ammonites, Moabites, and even, for the most part, Israelites from the Northern Kingdom. Only Judah emerged intact as a coherent people after years of occupation and exile. How did they manage to survive while their neighbors around them didn't? A large part of the answer is reflected in today's reading from Isaiah. "Have you not known? Have you not heard? . . . Lift up your eyes on high and see: Who created these? He who brings out their host and numbers them, calling them all by name; because he is great in strength, mighty in power, not one is missing." It was common in the ancient world to interpret the conquest of one nation by another as the victory of one god (or set of gods) over another. If one's national gods were weak, people reasoned, perhaps it would be better to worship the gods of the conquerors. The Jews had a different idea. Although they had been defeated by the Babylonians, they interpreted their troubles not as an indication of God's weakness but as an indication of their own sins. In contrast to the diminishing value many nations placed on their gods after they were conquered, the Jews' estimation of God did nothing but grow during the exile. Of particular importance was their growing understanding of their God not as a national God alone but as God of the whole world, even its creator. Accepting the idea, proclaimed by the exilic prophets, that their God was the creator of the world as well as their national deliverer allowed the Jews to flourish under difficult circumstances, endure the years of exile, and emerge as a stronger people. Over the centuries the Jews have faced many other threats to their existence--the war with Antiochus Epiphanes, the First and Second Jewish Wars with the Romans, the expulsion of Jews from Spain, and the Holocaust--but their faith in God as creator of the world, a God who also loves and sustains them and calls them to follow God's will, has preserved them through the centuries. Christians owe their very existence to the prophets of the exile who proclaimed a new vision of God and to the people who took that understanding of God to heart. Today it is our duty to proclaim God as one who not only created the world in the past and sustains it in the present, but as one who will redeem it in the future. If we lose this vision, despite our present numerical dominance among the world's religions, we will be in danger of succumbing to the fate of the Philistines and their neighbors, whose gods were not able to provide them with a reason to exist.

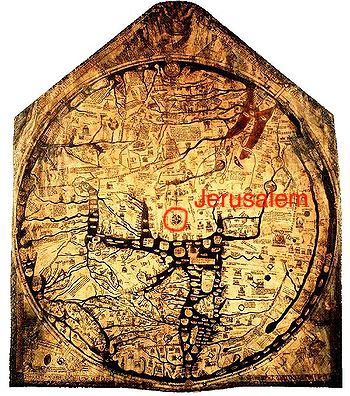

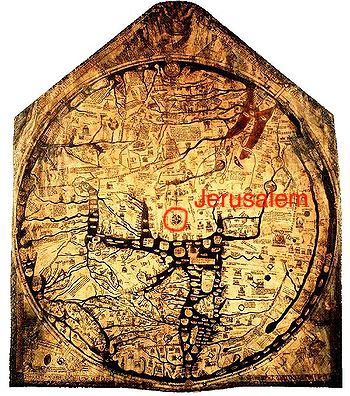

On the wall of Hereford Cathedral in Herefordshire, England, a few kilometers from the Welsh border, hangs one of the most ancient maps, and the largest surviving map, depicting the entire world. The Hereford Mappa Mundi was created about the year 1300 on a single piece of calfskin. It presents the known world as surrounded by a circular ocean and divided by the Mediterranean Sea into three continents: Europe, Africa, and Asia. Right in the center of the map is Jerusalem, surmounted by a crucifix. Any modern person looking at this map would be hard pressed to find much correspondence between actual geographical shape and cartographic representation. People in the ancient world would have had the same problem. This Mappa Mundi, and others like it, use a kind of sacred, rather than realistic, geography. Jerusalem, founded by the Canaanites, conquered by David and used as his capital, overrun by the Babylonians, ruled over by the Persians, Greeks, and Romans, swept up in the Muslim conquests, captured and then lost by Crusaders, supervised by Great Britain, and today claimed by both Israelis and Palestinians, is not, nor ever has been, the city of a single religion. From the Jebusites who survived David's conquest, to the court diplomats of the royal period (not to mention Solomon's foreign wives), to the Greeks who continued to occupy portions of the city in Maccabean times, to the Jews, Christians, and Muslims who at one time or another have lived alongside each other over the past two millennia as sometime majority, sometime minority populations, Jerusalem has always been a city that held a special place in the hearts of many different people. The psalmist says, "The Lord builds up Jerusalem; he gathers the outcasts of Israel. He heals the brokenhearted, and binds up their wounds." Too often when people today think of Jerusalem, they think of a city in conflict. Worse yet, they think of a city that belongs, or ought to belong, to one religious faction to the exclusion of all others. It's much better to think of Jerusalem as a place where all are welcome, including outcasts and strangers. It is a place of healing, of rest, of community. It is a place of reconciliation and peace. It is not necessarily the literal city of Jerusalem--though it would be great if it evolved into such a place--but it is an idea, a creation of the heart and spirit. It is a church, a mosque, a synagogue, a temple, a home, a park, a gathering on the national mall. It is wherever and whenever all God's children gather and love one another. Places like that, like Jerusalem on the Mappa Mundi, are the true centers of the world.

1 Corinthians 9:16-23 (first published 5 February 2006)

Turn on the television at any time of the day or night, switch to

certain Christian stations, and you'll see rich, well-dressed

televangelists preaching a message that goes something like this: "God

wants you to be wealthy. God wants you to be healthy. You can measure

your spiritual wellbeing to a large extent by looking at your bank

account. Give to my ministry and God will bless you!" Many, perhaps

most, of these televangelists have gotten rich off of the donations of

their supporters. Like the peddlers of indulgences in the time of Martin

Luther, they continue to bilk the people of their money with promises of

spiritual rewards. Unlike Tetzel and his compatriots, however, many of

today's televangelists, as well as others in leadership positions who

preach a similar message, grow rich from the contributions of their

followers. In his letter to the church at Corinth, Paul provides a better

model for ministry. "What then is my reward? Just this: that in my

proclamation I may make the gospel free of charge, so as not to make full

use of my rights in the gospel." For Paul, preaching the good news of

Jesus Christ was an obligation that he felt in the depths of his soul.

When he remembered his persecution of the church years earlier, he was

overcome by the magnanimity of God's grace and forgiveness, and he had to

share the message with others. Paul even modified his message somewhat,

without altering the essentials, in order to persuade Jews and Gentiles

alike of the joys that awaited them in the Christian life. For people who

have been followers of Christ for years, particularly for those of us who

have resisted some of life's more frowned-upon temptations, it is easy to

fall into a sense of complacency and even moral superiority. We begin to

see ourselves as better than the masses of "rabble" that inhabit our inner

cities. We look down our noses at ex-cons, drug addicts, and panhandlers.

We may even begin to feel a sense of entitlement, as though we had somehow

earned the comforts of life by our inherent goodness or righteousness.

Whenever we begin to feel this way, we need to listen again to Paul,

follow his ministry model, and above all, feel his sense of wonder that

God cares for us.

Mark 1:29-39 (first published 5 February 2006)

The Hajj, the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, concluded recently. About two million Muslims from all over the world descended on Mecca in order to fulfill one of their religion's most important rites. For many, it was a once in a lifetime experience that they will remember for the rest of their lives. I have often heard Christians say, "Why should I go on a mission trip with my church out of town or out of the country? There are plenty of people right here in [insert name of city] who need ministry." I've also noticed that most of the people who say that don't get involved in any of the church's local ministries to people, either. It's certainly true that ministry opportunities abound in any area, urban, suburban, or rural. It is also the case that there are people who, because of health issues, lack of financial resources, job requirements, or family dynamics cannot take extended mission trips away from home. However, I think that people who have the opportunity and are able to do so should take at least one mission trip sometime in their lives. I've had the opportunity to go on several mission trips, both in and out of the country, over the course of my life, and for the past several years I've gone with a group of people to Honduras to work with rural inhabitants of the department (state) of Olancho. I'll never forget my first visit to the ranch where we stayed during the week. One of our trip leaders asked us why we came to Honduras. After listening to various responses from the group, he made a comment that touched me deeply. "We sometimes think of mission trips like this as an opportunity to come to a foreign country and save the people there," he said, "but that's not it at all. We don't come to Honduras to save others. We come to Honduras to save ourselves." In today's reading from Mark, Jesus comes to Peter's house, heals his mother-in-law, then spends the rest of the night healing and casting out demons. If he had wanted to, Jesus could have set up shop right there in Capernaum and made a reputation for himself as a healer, but that's not what he does. Instead, early the next morning Jesus gets up and goes out into the wilderness to pray. When his disciples find him, they ask him to come back to the city to continue the healing ministry. "You're a hit!" they might have told him. "You're popular. This has the makings of a great ministry!" "No," Jesus said, "let's go to the neighboring towns, because that's what I came out to do." Jesus understood that his ministry was bigger than a single town, even a single large city. He couldn't visit every city in Israel, much less in the world, in his lifetime, but he saw value in an itinerant rather than a purely localized ministry. I don't believe that everyone is called to travel the globe with the gospel message, but I do think that we must think in global terms. We can't do that, however, if the only perspective we have is our own city, or even our own neighborhood and routines. Seeing other parts of the country, and especially other parts of the world, will remind us that our little community reflects neither the diversity nor the need of the world as a whole. We can't solve all the world's problems, nor can we preach God's good news to everyone on the planet, are we're not called to do that. In fact, I think that's the wrong way to look at a mission trip or other opportunity to travel. Yes, we have something to contribute, but we have just as much, and probably more, to learn from the people we visit in other places. We may take them hope, but they can show us faithfulness. We may take them material riches, but they can show us spiritual riches. We may take them a message, but they can show us humility. It's not that the poor around the world are better than we are or closer to God. It's that they have experienced life in ways that we never have, and they have more in common with the majority of the human race than we ever will. God calls us to follow the example of Jesus in an itinerant ministry. As we go, we must be faithful in sharing the wisdom and the riches that God has granted us, but we must also be willing to learn from those to whom we minister, for they have just as much to offer us as we have to offer them.